April 17, 2011

Sitert

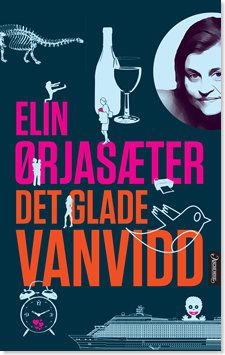

Jeg er sitert på omslaget av Elin Ørjasæters bok Det glade vanvidd (2. opplag).

For å finne ut hva jeg mener, les hele bloggposten jeg skrev om boken.

Og les boken selvfølgelig.

Posted by Julie at 12:51 PM | TrackBack

April 6, 2011

Not leaving

You may well wonder why I wanted Boris at all, a man who tells his still-wife that he's shacking up with his new squeeze for "practical reasons", as if this shocking new arrangement is simply a matter of New York real estate. I wondered why I wanted him myself. Had Boris left me after two years or even ten, the damage would have been considerably less. Thirty years is a long time, and a marriage acquires an ingrown, almost incestuous quality, with complex rhythms of feeling, dialogue and associations. We had come to the point where listening to a story or anecdote at a dinner party would simultaniously prompt the same thought in our two heads, and it was simply a matter of which one of us would articulate it first. Our memories had also begun to mingle. Boris would swear up and down that he was the one who came upon the great blue heron standing on the doorstep of the house we rented in Maine, and I am just as certain that I saw the enormous bird alone and told him about it. There is no answer to the riddle, no documentation - just the flimsy, shifting tissue of remembering and imagining. One of us had listened to the other tell the story, had seen in his or her mind the encounter with the bird, and had created a memory from the mental images that accompanied the heard narrative. Inside and outside are easily confused. You and I. Boris and Mia.

- From The Summer Without Men by Siri Hustvedt.

Siri Hustvedt's The Summer Without Men starts with Boris leaving Mia, and follows Mia's summer of interacting only with women. It's about mothers and daughters, old friends, new friends, and the cruelty of teenage girls. And it's about what happens when your Most Important Person over the last thirty years just leaves.

I haven't known anyone for thirty years, for obvious reasons. But as always, Hustvedt's characters seem so real that I find myself relating to them anyway. I told my mom - who's known my dad since they were seventeen - the story of the heron, and she could relate.

And I can certainly understand the feeling of losing part of yourself when you lose an Important Person. Or rather, feeling like you can't let that person go, because even if you never see them again, your personalities are so entwined that they will always be with you - in your memories, your associations, your tastes, in the way your mind works.

In another book I recently read, love was defined like this: "Love means not leaving." Maybe it is that simple.

More posts about Hustvedt's books:

- Nye venner fra Hustvedt (my review of Sorrows of an American, in Norwegian)

- Reuniting with Leo

Image: icanread

Posted by Julie at 10:51 AM | TrackBack

March 22, 2011

Stein fra glasshus

Å lese Elin Ørjasæters nyeste bok, Det glade vanvidd, føles som å lese hele arkivet til en blogg på én dag: Den er en samling relativt korte meningsbærende tekster hvis eneste åpenbare sammenheng er at de har samme jeg-person. Her er hva Elin mener om tårer, foreldremøter, psykiske diagnoser, cruise, kosmetisk kirurgi, vinterferie og telegiro (faktisk). Det er velskrevet, og - siden jeg i E24 til tider fungerer som Elins korrekturleser legger jeg merke til dette - med påfallende få språkfeil. Men etter noen sider har jeg en potensielt bitende kritikk klar: Hva er nå poenget med dette da? Man skal være ganske interessert i Elin personlig for å skjønne vitsen.

Å lese Elin Ørjasæters nyeste bok, Det glade vanvidd, føles som å lese hele arkivet til en blogg på én dag: Den er en samling relativt korte meningsbærende tekster hvis eneste åpenbare sammenheng er at de har samme jeg-person. Her er hva Elin mener om tårer, foreldremøter, psykiske diagnoser, cruise, kosmetisk kirurgi, vinterferie og telegiro (faktisk). Det er velskrevet, og - siden jeg i E24 til tider fungerer som Elins korrekturleser legger jeg merke til dette - med påfallende få språkfeil. Men etter noen sider har jeg en potensielt bitende kritikk klar: Hva er nå poenget med dette da? Man skal være ganske interessert i Elin personlig for å skjønne vitsen.

Dette blir imidlertid ingen bitende kritikk. For gradvis går det opp for meg at gjennom tabloide formuleringer og personlige anekdoter trykker Elin på et ømt punkt hos meg, et blåmerke jeg har sminket over så lenge at jeg ikke lenger kjenner det igjen når jeg ser det.

"Moderskapet er alle kvinners, også feministers, såre punkt. Stikk oss her, og vi er forsvarsløse," skriver Elin.

På dette tidspunktet - side 52 - har Elin presentert leseren for forskerkvinnen, næringslivskvinnen, grunderkvinnen og kvinnene som gråter (det vil si de fleste av oss, selv om det ikke gir oss mer rett i konflikter. Mer om det senere). Fellesnevneren er rollesjongleringen kvinner driver med.

Det er her tekstene kommer litt for nært ting jeg prøver å ikke tenke for mye på.

Jeg er vokst opp med en pappa som først var doktorgradsstudent (altså alltid opptatt) og så foreleser/førsteamanuensis/konsulent/skribent/blogger (altså fortsatt alltid opptatt). Og en mamma som var hjemme. Pappa jobbet 200%. Pappa var kanskje i Kina, kanskje i India, kanskje inne på hjemmekontoret - jeg hadde ikke helt oversikt. Pappa måtte ikke forstyrres fordi han skulle ta eksamen. Mamma kunne høre hvordan dagen min hadde gått på hvordan jeg åpnet inngangsdøren. Mamma sørget for at jeg hadde hjemmebakt brød i matpakken (amerikanere kan ikke grovbrød). Mamma farget klærne mine fordi ingen butikker solgte svarte barneklær og sydde kostymer uansett hva jeg ville kle meg ut som. Mamma var alltid tilgjengelig.

I A-magasinet svarer en leser på et intervju med Elin: "Hun tør å si at hun angrer på at hun valgte karriere fremfor barna, det er det ikke mange som gjør. Jeg er en firebarnsmor som har valgt barn og familie fremfor karriere, og jeg er lei av alle disse karrieremammaene som alltid klager på dårlig tid, rekker ikke ditt, rekker ikke datt. Jeg får alltid høre: "Så rolige barn du har, hva har dere gjort?" - Hallo! Vi er der for dem, de trenger ikke streve etter oppmerksomhet!"

Og når jeg leser sånt, får jeg vondt i magen. Jeg kan ikke være hjemme med barn. Jeg blir rastløs av å være i min egen leilighet én dag. På mange måter håper jeg at jeg blir som foreldrene mine, men jeg kommer ikke til å rekke å være som dem begge på en gang. Og hvis jeg måtte valgt i dag, ville jeg blitt som pappa når jeg blir stor. Fordi jeg oppriktig tror at å være hjemmeværende ville gjort meg deprimert.

Og når jeg leser sånt, får jeg vondt i magen. Jeg kan ikke være hjemme med barn. Jeg blir rastløs av å være i min egen leilighet én dag. På mange måter håper jeg at jeg blir som foreldrene mine, men jeg kommer ikke til å rekke å være som dem begge på en gang. Og hvis jeg måtte valgt i dag, ville jeg blitt som pappa når jeg blir stor. Fordi jeg oppriktig tror at å være hjemmeværende ville gjort meg deprimert.

Nå representerer foreldrene mine motsatt side av en skala der de fleste norske kvinner i dag befinner seg nærmere midten. Utfordringen min kommer til å være å finne en balanse mellom de egenskapene jeg beundrer hos hver av dem.

Og det er nettopp det jeg kommer til å ta med meg fra Elins bok: Hun innrømmer at dette er en utfordring. At akkurat disse problemstillingene er vanskeligere for kvinner enn for menn, og at selv om det er blitt bedre, er det fortsatt ikke perfekt.

Alternativt kan man si at bokens poeng er å finne på side 138, der Elin skriver "Det er en dyd å ta seg sammen." Boken er et eneste stort SKJERP DEG! til overfølsomme, hypersensitive, politisk korrekte mennesker med diverse vage diagnoser. Og til meg, som sitter her og bekymrer meg for en hjem/karriere-balanse som (potensielt) ligger mange år inn i min egen fremtid.

Og til Elin selv, for hun er heldigvis klar over det når hun sitter i glasshus. Hun skriver for eksempel at alt kan spøkes med, unntatt det hun selv tar seg nær av.

Stein fra glasshus var en mulig tittel på boken, og jeg mener fortsatt at den ville vært bedre enn Det glade vanvidd.

Kvinner som holder hverandre nede nettopp ved å insistere på at kvinner alltid skal holde sammen, kaster stein fra glasshus. Kvinner som vil bli tatt på alvor, men som likevel prøver å bruke egne tårer som argument i diskusjoner, gjør også det. Norske, høyt utdannede kvinner med god jobb og et godt familieliv som klager på at det er så vanskelig å være kvinne, sitter definitivt i glasshus - men hvem har sagt at glasshus er noe bra sted å være?

Jeg mener bestemt at jeg gjør langt mer for likestilling ved å gjøre jobben min uavhengig av at jeg er kvinne, enn ved å bruke store deler av min tid på å snakke om at det er vanskelig å være kvinne og gjøre jobben min. Her om dagen sa jeg til en gutt: "Jeg er så lei av å høre at jeg er undertrykket. Det er faktisk ikke så vanskelig å være jente."

Men det er befriende når noen innrømmer at det er vanskelig innimellom likevel: At det for eksempel gjør vondt å reise fra barna sine for å dra på jobb ("Biologi kan overvinnes, men det er ikke spesielt trivelig mens det pågår.") Det kan være sterkt når noen som vanligvis er beinharde på å skille person og sak tør å skrive hva de føler.

Men det er befriende når noen innrømmer at det er vanskelig innimellom likevel: At det for eksempel gjør vondt å reise fra barna sine for å dra på jobb ("Biologi kan overvinnes, men det er ikke spesielt trivelig mens det pågår.") Det kan være sterkt når noen som vanligvis er beinharde på å skille person og sak tør å skrive hva de føler.

Det hele bindes sammen i siste kapittel, "Verden", der Elin hever diskusjonen hun fører med seg selv til et globalt perspektiv. Riktig nok ved å beskrive egne erfaringer med cruise-ferie, men poenget kommer frem likevel: Vi profesjonaliserer husarbeid, og leier inn praktikanter med midlertidig oppholdstillatelse til å utføre de oppgavene vi ikke vil gjøre selv. Så kan vi få tid til både karriere og barn, mens damene som vasker gulvene og serverer drinkene våre føler seg heldige om de ser barna sine to ganger i året. Alle vil ha hushjelp, ingen vil at datteren deres skal bli hushjelp, og likestilling kan dermed gjenninnføre klassesamfunnet i Norge, nå med en internasjonal vri.

Det tok meg et par timer å lese boken - og over en uke å formulere hva jeg tenkte mens jeg leste. Ikke fordi den gjør noe som helst forsøk på å være dyp, men fordi jeg ikke liker å innrømme at jeg er bekymret for å ikke klare å gjøre som mamma. Det er greiest når andre innrømmer sånt, så kan jeg bare lese det andre skriver. Så ja, boken er som en samling bloggposter. Men fra en blogg jeg ville ha fulgt med på.

Illustrasjoner: Aschehoug, PostSecret, acunat, lorenia (Creative Commons)

Les også:

Posted by Julie at 5:01 PM | Comments (5) | TrackBack

December 6, 2010

Dagens blogger: jill/txt

Det er 6. desember, og vi bør lese bloggen jill/txt. Jeg skriver "vi" fordi jeg også burde lese mer av henne, det vil si Jill Walker Rettberg.

Hvorfor har ikke internett presentert meg for henne før? All logikk tilsier at jeg burde ha støtt på henne i en eller annen sammenheng: Hun har blogget siden 2000, mye om litteratur og digitale medier, som jeg nerder om, og på en blanding av norsk og engelsk, som meg. I tillegg har hun vokst opp i et engelskspråklig land, som meg. Og hun bruker (finner på?) begreper som digital multiculturalism. Jeg burde ha lest henne fast siden videregående. I stedet begynte jeg for noen dager siden, da jeg snublet over henne via Virrvarr (også en bra blogg selvsagt, men det er en annen historie). Jeg kunne selvsagt valgt å føle meg uvitende, men jeg velger å holde internett kollektivt ansvarlig for at jeg ikke har "møtt" denne bloggen før.

Jill blogger ikke så ofte for tiden, men nok til at nettsiden er langt fra død. Bloggen er dessuten et arkiv over fagfeltet digital litteratur. Det understreker forsåvidt poenget fra denne bloggposten: Twitter er kjempegøy, men det er samtidig et medium med irriterende kort hukommelse (overskriften her oppsummerer det uten å egentlig mene det).

Dessuten er det behagelig å lese om sosiale/digitale medier i en litterær sammenheng. Noen ganger blir jeg lei av å snakke om hvordan aviskonsern skal tjene penger i fremtiden eller hvordan bedrifter best kan fremstille seg selv i sosiale medier. Blogging og andre former for digitale medier handler også om å fortelle historier. Kanskje først og fremst om det.

Og hvis noen av mine kjære nerdevenner trenger et konkret bevis for at Jill Walker Rettberg bør leses: Hun har redigert en vitenskapelig antologi om World of Warcraft.

Blogg: jill/txt

Twitter: @jilltxt

Utvalgte innlegg

Jilltxt presenterer sin forskning i videoform

Teaching kids about censorware and privacy - inkl. omtale av Cory Doctorows Little Brother

Blogging about cancer - hvorfor så mange blogger handler om sykdom

Posted by Julie at 8:44 PM | TrackBack

December 5, 2010

Book list

Have you read more than 6 of these books? The BBC believes most people will have read only 6 of the 100 books listed here. Instructions: Copy this into your notes. Bold those books you’ve read in their entirety, italicise the ones you started but didn’t finish or read an excerpt. Tag other book nerds.

1 Pride and Prejudice - Jane Austen

2 The Lord of the Rings - JRR Tolkien

3 Jane Eyre - Charlotte Bronte

4 Harry Potter series - JK Rowling

5 To Kill a Mockingbird - Harper Lee

6 The Bible

7 Wuthering Heights - Emily Bronte

8 Nineteen Eighty Four - George Orwell

9 His Dark Materials - Philip Pullman

10 Great Expectations - Charles Dickens

11 Little Women - Louisa M Alcott

12 Tess of the D’Urbervilles - Thomas Hardy

13 Catch 22 - Joseph Heller

14 Complete Works of Shakespeare

15 Rebecca - Daphne Du Maurier

16 The Hobbit - JRR Tolkien

17 Birdsong - Sebastian Faulk

18 Catcher in the Rye - JD Salinger

19 The Time Traveller’s Wife - Audrey Niffenegger

20 Middlemarch - George Eliot

21 Gone With The Wind - Margaret Mitchell

22 The Great Gatsby - F Scott Fitzgerald

23 Bleak House - Charles Dickens

24 War and Peace - Leo Tolstoy

25 The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy - Douglas Adams

26 Brideshead Revisited - Evelyn Waugh

27 Crime and Punishment - Fyodor Dostoyevsky

28 Grapes of Wrath - John Steinbeck

29 Alice in Wonderland - Lewis Carroll

30 The Wind in the Willows - Kenneth Grahame

31 Anna Karenina - Leo Tolstoy

32 David Copperfield - Charles Dickens

33 Chronicles of Narnia - CS Lewis

34 Emma - Jane Austen

35 Persuasion - Jane Austen

36 The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe - CS Lewis

37 The Kite Runner - Khaled Hosseini

38 Captain Corelli’s Mandolin - Louis De Bernieres

39 Memoirs of a Geisha - Arthur Golden

40 Winnie the Pooh - AA Milne

41 Animal Farm - George Orwell

42 The Da Vinci Code - Dan Brown

43 One Hundred Years of Solitude - Gabriel Garcia Marquez

44 A Prayer for Owen Meany - John Irving

45 The Woman in White - Wilkie Collins

46 Anne of Green Gables - LM Montgomery

47 Far From The Madding Crowd - Thomas Hardy

48 The Handmaid’s Tale - Margaret Atwood

49 Lord of the Flies - William Golding

50 Atonement - Ian McEwan

51 Life of Pi - Yann Martel

52 Dune - Frank Herbert

53 Cold Comfort Farm - Stella Gibbons

54 Sense and Sensibility - Jane Austen

55 A Suitable Boy - Vikram Seth

56 The Shadow of the Wind - Carlos Ruiz Zifon

57 A Tale Of Two Cities - Charles Dickens

58 Brave New World - Aldous Huxley

59 The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time - Mark Haddon

60 Love In The Time Of Cholera - Gabriel Garcia Marquez

61 Of Mice and Men - John Steinbeck

62 Lolita - Vladimir Nabokov

63 The Secret History - Donna Tartt

64 The Lovely Bones - Alice Sebold

65 Count of Monte Cristo - Alexandre Dumas

66 On The Road - Jack Kerouac

67 Jude the Obscure - Thomas Hardy

68 Bridget Jones’s Diary - Helen Fielding

69 Midnight’s Children - Salman Rushdie

70 Moby Dick - Herman Melville

71 Oliver Twist - Charles Dickens

72 Dracula - Bram Stoker

73 The Secret Garden - Frances Hodgson Burnett

74 Notes From A Small Island - Bill Bryson

75 Ulysses - James Joyce

76 The Inferno - Dante

77 Swallows and Amazons - Arthur Ransome

78 Germinal - Emile Zola

79 Vanity Fair - William Makepeace Thackeray

80 Possession - AS Byatt

81 A Christmas Carol - Charles Dickens

82 Cloud Atlas - David Mitchell

83 The Color Purple - Alice Walker

84 The Remains of the Day - Kazuo Ishiguro

85 Madame Bovary - Gustave Flaubert

86 A Fine Balance - Rohinton Mistry

87 Charlotte’s Web - EB White

88 The Five People You Meet In Heaven - Mitch Albom

89 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes - Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (reading it right now)

90 The Faraway Tree Collection - Enid Blyton

91 Heart of Darkness - Joseph Conrad

92 The Little Prince - Antoine De Saint-Exupery

93 The Wasp Factory - Iain Banks

94 Watership Down - Richard Adams

95 A Confederacy of Dunces - John Kennedy Toole

96 A Town Like Alice - Nevil Shute

97 The Three Musketeers - Alexandre Dumas

98 Hamlet - William Shakespeare

99 Charlie and the Chocolate Factoy - Roald Dahl

100 Les Miserables - Victor Hugo

Book nerds! What have you read?

Posted by Julie at 5:04 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

July 26, 2010

The secret city underneath Paris

To go underground and discover what lies buried beneath Paris, read this.

And then I'll tell you why I wanted you to do so...

I read The Lizard, the Catacombs, and the Clock: The Story of Paris’s Most Secret Underground Society because it was tweeted by Roger Ebert, so it was probably interesting. I had no idea what to expect, except that it would be about Paris and mysteries. Half way through I realized that I didn't even know if what I was reading was true. Was it journalism with literary influences or a short story meant to read like a feature article? It was published in a literary magazine, so was this fiction or non-fiction? I didn't care. I felt like I was reading a short novel. I wanted it to be a longer novel. I wanted someone to make it into a movie. I was imagining the trailer, with smoke drifting around Parisian street corners as members of a secret society emerge from potholes at 5 in the morning, holding hands. The layers of secrecy and confusion of art and reality reminded me of Siri Hustvedt's parallell universe. The journalist didn't know if the sources could be trusted, and as a reader, I didn't know if I could trust my narrator, but I was happy to go along with it all. I wanted to be tricked into believing that if I had just known the right people or taken the right wrong turn in the metro system, I would have discovered a dark and dusty Narnia. I wanted to believe - not know, believe - that there are people who secretly maintain the city of Paris from within.

"I have reached a dead end. Lanso’s secrets are tantalizing, but I can neither confirm nor deny them. UX’s deepest riddles cannot be Googled. The question I ask is, Do I believe them? And then I ask, Do I want to believe them? And then I know my answer."

Image: Zoriah, Creative Commons

Posted by Julie at 10:19 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

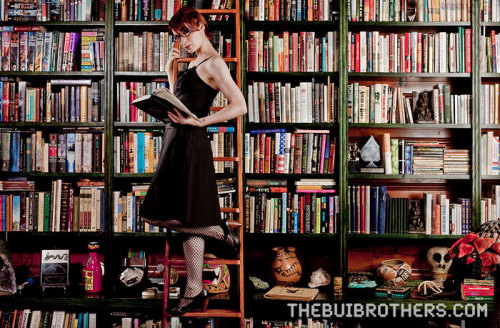

July 7, 2010

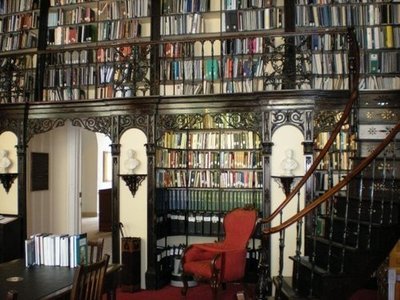

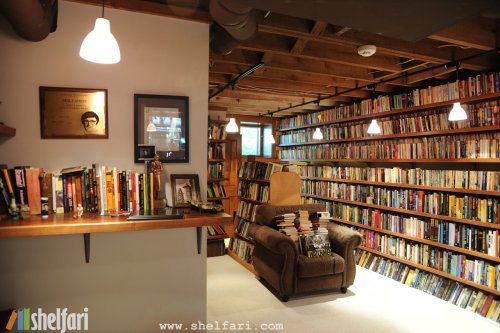

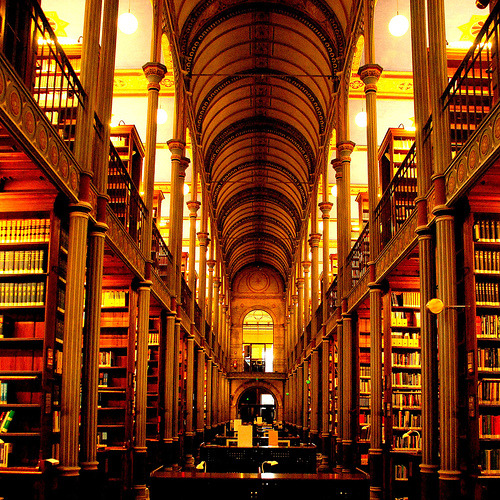

Library fantasies

With one exception (the glasses) the photo below could basically be me in my living room. The more books in a room, the happier I am. But lately I've been spending my free time packing my books into boxes. I'm moving soon, and it is highly unlikely that I will have room for my entire library in my next home. Sigh. In between sorting books into labeled cardboard boxes (Books I Absolutely Must Put On Shelf In Smaller Apartment, Books I Will Reluctantly Relocate To Parents' Attic, Utterly Useless PoliSci Textbooks Whose Pages Can Be Used To Wrap Coffee Cups, Books I Stole From Dad Years Ago, Books I Really Should Return To Ex/Acquintance/That Guy/Despicable Creature Who Absolutely Does Not Deserve Them, Books I Should Just Carry Around In Purses Until I've Read Them Again etc.), I've edited a magazine article about BookCrossing. It's by Marit Letnes, will be published in the next issue of argument, and (spoiler!) contains paragraphs like:

"Books are special objects, carriers of culture, not to be thrown away lightly. Destruction of books is often taboo, as if they have a spirit. They are not like other commodities: They should be given, not just sold."

Hardly the right sentences for me to be repeating over and over in my head when I should be thinking about letting go of my books.

So I fantasize about libraries. So does @nongenderous apparently. Her tumblr is full of library pictures. Read/dream on...

I love the feeling of promise that comes with a library.

Aahh... No comment necessary. I could live here.

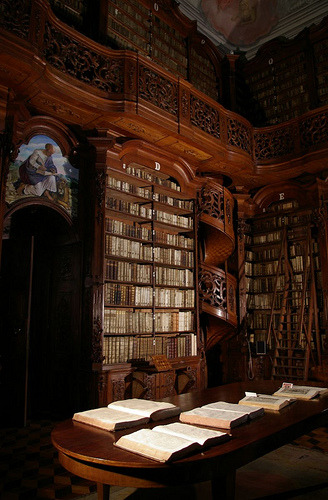

I could live here too, although it is a little too church-like. Who is the monk-like guy above the door? Where is this?

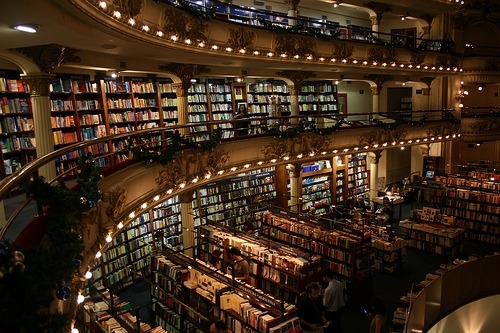

El Ateneo in Buenos Aires, a bookstore in a theater.

Nice. I have no idea where this is either.

Neil Gaiman's bookshelves. See more from his collection here.

The University of Copenhagen. One should consider the inspirational value of the university library when choosing a university. (Photo by Bo Madsen, I think)

Oh... wow. Biblioteca Joanina, at the University of Coimbra. Too bad I can't read Portugese. (My own university library wasn't ugly, but I probably should have gone to Copenhagen or Coimbra.)

In the process of moving, this is a more realistic idea of what my library looks like.

(All images via nongenderous. Original locations and photographers are usually lost on tumblr, but if you know where the photos are from, please let me know so I can credit and link appropriately. And visit the libraries of course.)

Posted by Julie at 11:32 PM | TrackBack

June 29, 2010

Generasjon Facebook - endelig en bok om meg!

Jeg kunne umulig ha lest boken Generasjon Facebook eller Da alle skulle bli noe med media av Jon Niklas Rønning på et bedre tidspunkt enn nå. Nettopp ferdig med en journalistutdanning, fast bestemt på å bli noe med media, kjøpte jeg boken fordi jeg tenkte at jeg kunne blogge om den.

Jeg følte meg som hovedpersonen i Groundhog Day (Me, me, me also... I am really close on this one) da jeg leste beskrivelsene av hvordan "vi som vokste opp på 90-tallet" nå bor i bittesmå Oslo-leiligheter med litt for store prismelysekroner og drikker cortado på café mens vi diskuterer amerikansk politikk og våre egne skyhøye ambisjoner. Ja, jeg har oppdatert Facebook-profilen min for å fortelle at jeg er vÃ¥ken. Ja, jeg vet nøyaktig hva som kommer opp når man googler "Julie R. Andersen". Og når Rønning skriver "Det er merkelig hvor bekymringsløst man kan feste, dersom man føler man allerede har nådd selve livsmåletuot; eller "Hvorfor skjer det gang på gang - at vi på død og liv vil realisere de kreative sidene våre, men samtidig ikke setter av nok tid til å bli flinke?" eller "Du mangler inspirasjon, men skriver låter om det," tenker jeg: JA! Endelig har noen skrevet en bok om meg og alle jeg kjenner. I tilfelle jeg var i tvil, kunne Side2 bekrefte via en enkel test at selv om jeg strengt tatt er akkurat for ung til å skjønne 90-tallsreferansene, er jeg et medlem av Generasjon Facebook.

Mot slutten av boken står det: "Du vet du er en del av Generasjon Facebook når du irriterer deg over generaliseringer, og mener at du er mer unik enn stereotypiene som blir presentert i denne boka."

Den passet ikke. For de gangene det dukker opp generaliseringer jeg virkelig kjenner meg igjen i, blir jeg bare kjempeglad. Når jeg tar meg selv i å passe inn i en bås eller være en eller annen form for klisjé, er det underholdende, ikke flaut. Når jeg sitter på Café Sara med tre venninner og deler to flasker rødvin og én Klassekampen-artikkel om bibelreferansene i Tori Amos-tekster. Eller blir med på konsert med en liten gruppe nyutdannede designere og oppdager at vi alle matcher, fordi det er høsten 2009 og alle skal gå i mørkelilla og lysegrått. Eller retter på språket til foreleseren på Blindern og hører halve raden jeg sitter på hviske "den gang DA" i kor. Eller drar på "alternative" "indie" konserter med Regina Spektor eller Camera Obscura og blir overrasket over at halve klassen og alle jeg følger på Twitter også er der. Da tenker jeg "Nå er jeg så typisk _______(velg stereotyp selv)".

Det er egentlig rart at vi stadig får høre at vi skal være "oss selv", samtidig som vi alltid blir bedt om å beskrive oss selv ut fra hvilke båser vi passer inn i. De som vurderer å la meg bo i kollektivet sitt vil vite om jeg er A-menneske eller B-menneske, ryddig eller rotete, rolig eller ikke rolig. Jeg kan ikke svare på de spørsmålene. Det kommer an på.

Men jeg vet jo hvem jeg er, og jeg liker det når menneskene jeg møter er som meg. Ikke på alle punkter, men på mange punkter. Det er ikke fordi jeg er usikker eller trangsynt. Det er fordi jeg har opplevd å føle meg kjempespesiell og helt unik. Jeg har tenkt "ingen er som meg". Og det er ikke morsomt.

Har vi ikke alle vært der? Kanskje ikke, for jeg leser stadig intervjuer med folk som forteller at det er sykt viktig for dem å "være seg selv" og "skille seg ut". De som hele tiden må fortelle hvor spesielle de er, kan umulig være så spennende på ordentlig. Er du spesiell, kommer det frem uten at du trenger å bokstavere det.

Mitt slagord er kanskje det motsatte av det som står øverst i dette innlegget:

I like to think I'm like everyone else, but I guess that makes me unique.

Posted by Julie at 12:04 AM | TrackBack

May 19, 2010

Fashion lessons from childhood fiction

- Don’t be afraid of super high shoes. (Cruella de Vil)

- It’s not enough just to be pretty. (Jane Eyre)

- Well-tailored jackets and tiny Victorian-style boots go with everything. (Mary Poppins)

- There’s no shame in being different, bright jackets are awesome and you really need to stop judging people entirely by their clothing, even though judging people entirely by their clothing leads to completely accurate assumptions. Actually, every single item in your closet would look better surrounded by Parisian scenery... and judging people by their clothing is more accepted in Paris. (Madeline)

Via Jennifer Wright's series Fashion lessons from childhood fiction

Oh, and by the way, some related posts:

- Playing dress-up (how wanting to be a witch influenced my style)

- Dressed for anything (why Parisians judge)

- Style according to Julie (All my posts on clothes and fashion on one page)

(And yes, this was written as procrastination/break in the middle of writing a six page feature article on South African education. Yay, feature writing exams again!)

Posted by Julie at 9:55 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

January 15, 2010

Book review: The Big Questions

In The Big Questions, Steven E. Landsburg uses math, economics and physics to discuss questions of philosophy, especially morality and ethics.

In The Big Questions, Steven E. Landsburg uses math, economics and physics to discuss questions of philosophy, especially morality and ethics.

That sounds a lot more serious than the book turned out to be. In fact, Landsburg ends the book by saying that most of it was written "not to make any particular point but because it seemed to fit and I think it's interesting."

It's a good introduction to some basic econ, math and physics, and to Landsburg's own beliefs and guidelines on life (including the reasoning behind them). Many of the examples and anecdotes were old news to me, because I have already taken courses in math, physics, economics and philosophy. But it's well-written, entertaining and easy to read.

Favorites:

* If more people really and truly believed in the religions they claim to follow, they would behave differently. For example, why don't we have more suicide bombers? Landsburg concludes that hardly anyone is actually religious:

"If religious belief were as widespread as people claim it is, there should be millions upon millions of voluntary martyrs. (...) Believers in hell should commit fewer crimes; believers in heaven should take more risks; believers in one religion should interact in predictable ways with believers in another; believers in God should have a powerful interest in the alternatives. Those implications are testable. I am moderately confident that carefully gathered statistics would refute the hypothesis that religious beliefs are widely or deeply held."

* If you want to write, study something you love and write about it. Do not take writing classes:

"If your writing is murky, it's usually because your thinking is murky, too. The cure for that is not a series of writing exercises; it's to master your subject matter. (...) Prose flows easily when you understand what you're saying. If you're struggling to 'craft' your prose, you're probably confused."

* The Economist's Golden Rule: Don't leave the world worse off than you found it OR Don't spend valuable time and energy in non-productive ways. It follows that you should not steal, counterfeit or be an Olympic athlete:

"If you bake a cupcake, the world has one more cupcake. (...) But if you win an Olympic gold medal, the world will not have one more Olympic gold medalist. It will just have you instead of someone else."

Right:

Wrong:

(Cupcake by Kuidaore)

Posted by Julie at 2:52 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

August 12, 2009

City of Thieves

I've always envied people who sleep easily. Their brains must be cleaner, the floorboards of the skull well swept, all the little monsters closed up in a steamer trunk at the foot of the bed.

I was born an insomniac and that's the way I'll die, wasting thousands of hours along the way, longing for unconsciousness, longing for a rubber mallet to crack me in the head, not so hard, not hard enough to do any damage, just a good wack to put me down for the night. But that night I didn't have the chance. I stared into the blackness until the blackness blurred into gray, until the ceiling above me began to take form and the light from the east dribbled in through the narrow barred window that existed after all.

Only then did I realize that I still had a German knife strapped to my calf.

That was the end of chapter 2* in City of Thieves by David Benioff. The insomniac is imprisoned in Leningrad during the Nazi siege. His crime was looting a dead German soldier. His punishment was supposed to be death, but instead he is sent on a special mission to find 12 eggs so that a Soviet colonel's daughter can have a traditional wedding cake. In a city where people are willing to eat books - or each other - finding eggs is completely impossible. But it's the only way he can survive.

I read ten chapters of this book last night, so I expect to finish it by Friday. It's fast-paced, sad, scary and somehow funny.

*I have added paragraph breaks.

Posted by Julie at 9:58 AM | TrackBack

June 29, 2009

A twist on the espresso and books combo

Espresso machines can also access thousands of titles that are in the public domain and available on the Internet.

The quote is from D. C. Denison writing for The Boston Globe. Imagine if my espresso machine* could also provide me with literary classics. The espresso machine in question, however, is the Espresso Book Machine. And while that invention isn't news to me, this particular article made me consider how great an EBM at one of my local bookstores would be.

Because I love bookstores, and I love Amazon, and I don't want to have to choose. Being able to spend time, lots of time, staring at the shelves of a physical bookstore and then deciding that in addition to the stack of paperbacks I'm buying, I'd like to get some "out of print" titles too... ah, that would be something.

*It works now, btw. The problem turned out to be so simple that I was a bit embarrased when one of my espresso machine guys pointed it to me. But I did write "I will gladly humiliate myself online for good coffee," so I won't complain.

Oh, and by the way:

Posted by Julie at 9:30 PM | TrackBack

May 30, 2009

This week

Links for the weekend - Things I've been thinking about while writing for work.

This week I recommend Think again: Child soldiers from Foreign Policy, a very thought-provoking article.

Also thought-provoking is The New Socialism from Wired, where Kevin Kelly writes that social media is the new socialism. I'm not entirely sure what to make of this. While both my inner politics geek and my inner web-media geek are very pleased, I'm not sure the arguments in this article are all that original or even true. At any rate, thoughts on the behavioral economics of blogging, twittering and youtubing are interesting. Specifically, it's hard to think that I'm blogging with a strictly rational-choice what's-in-it-for-me attitude. The idea of blogging to contribute to a community makes more sense. With me, I tend to blog what's in my head anyway; it's really not work that I selflessly do for your benefit. In Norway, there's a twist to this web socialism, as our Labor Party prime minister twitters. When he announced this on radio, he claimed he would follow everyone who followed him, because that's the Labor Party way ("Alle skal med!"). I don't know if he kept his promise though - is he following me?

Speaking of social media, AudioBoo is the new thing, according to various sources, but I'm linking to The Guardian.

Speaking of social media, AudioBoo is the new thing, according to various sources, but I'm linking to The Guardian.

Going back to paper media, Dan Sabbagh at Times Online explains why the very snobby Monocle magazine is making money.

So it's not all doom and gloom: Global newspaper sales went UP in 2008.

But I still think paper is for art, not news. Examples to the left and above.

For Norwegian-speakers: B-mennesker er de nye A-mennesker fordi vi holder ut lenger.

This week I looked forward to Stuart Murdoch from Belle & Sebastian starting a girl group, God Help the Girl:

Although the dark-haired singer is clearly wearing my coat in this picture, I'm optimistic about this. I didn't love the first single (video), but I might in the near future. Individual Belle & Sebastian songs usually start out feeling anonymous, but then they grow on me.

This week I read The Enchantment of Lily Dahl by Siri Hustvedt.

I recently renewed my subscription to Morgenbladet, but they keep calling me and sending me multiple postcards urging me to renew my subscription. They need to get their act together. Despite subscribing, I can't link to them, which is beyond annoying.

I recently renewed my subscription to Morgenbladet, but they keep calling me and sending me multiple postcards urging me to renew my subscription. They need to get their act together. Despite subscribing, I can't link to them, which is beyond annoying.

I added a new personal blog to my Bloglines: Thoughts and All

Also: I HAVE TICKETS TO SEE TORI!

Posted by Julie at 2:54 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

May 21, 2009

Emergency Sex

That's a book title I felt a little bit weird reading on the subway.

Emergency Sex (and other desperate measures) is the autobiographical story of UN workers Kenneth Cain, Heidi Postlewait and Andrew Thomson. The three friends, who take turns being narrator, met in Phnom Penh in 1990. They stayed in touch as they worked for the UN in Cambodia, Haiti, Rwanda, Liberia and Bosnia throughout the violent nineties.

"Andrew wanted to bind the wounds of innocent war victims, hoping to find grace. Heidi embraced the freedom-born-of-emergency determined to liberate herself and, in the process, as many women as she could touch. I planned to harness the power of an ascendant America to personally undo the Holocaust. Don't laugh. We were young." - Kenneth Cain, Brooklyn, New York, April 2003

I've always felt that since people have endured so much suffering, and others have had to witness peoples' suffering first-hand, the least I can do is read about it years later without giving up. But unfortunately - perhaps fortunately, as it's probably a sign of sanity - reading novel-length texts about torture, war, fear and despair is simply no fun.

With this book, however, I never considered giving up. It's fast-paced to the point of feeling like it's written for the screen, but more importantly, the characters are real people. It's a true story not just because it's non-fiction, but because it includes the narrators' mistakes, doubts, pre-peacekeeping past, parties - and yes, their hook-ups. They're journal-writers, not feature reporters. The lighthearted anecdotes are a necessary break from the sometimes disgusting descriptions of violence, but they also provide a backdrop that feels realistic to me: You clean up the mess after unspeakable terror by day, but when night falls, you still have crushes, friendships and a need to unwind and lead a kind of life.

Posted by Julie at 12:33 AM | TrackBack

May 4, 2009

Første dag i TU!

Og etter litt teknisk rot og mange nye fjes å huske på, fikk jeg til og med publisert noe. Nemlig en artikkel om mulighetene for avislesing med e-bokteknologi.

Jeg har etterhvert skrevet mye om e-bøker:

Posted by Julie at 10:03 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

Today weblogs, tomorrow booklogs

"(...) readers will stumble across books through a particularly well-linked quote on page 157, instead of an interesting cover on display at the bookstore."

Author Steven Johnson predicts booklogs, blogs that link to books, in a future with e-books.

Posted by Julie at 8:23 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

March 13, 2009

Nye venner fra Hustvedt

Bokanmeldelse av Siri Hustvedts The Sorrows of an American:

Da Inga fortalte Erik at Leo skulle komme på festen, måtte jeg ta en pause i lesingen. Jeg måtte minne meg selv på at Leo er hovedpersonen i Siri Hustvedts forrige roman. Han er ikke en virkelig person som det er naturlig at jeg skal savne eller være bekymret for. Likevel ble jeg lettet og glad da han dukket opp på fest i The Sorrows of an American (på norsk: Når du ser meg).

Det er kanskje det beste en romanforfatter kan gjøre: å skape figurer som leseren oppriktig tror på. Faktisk så mye at vi har lyst til å ringe dem for å forsikre oss om at de har det bra selv om forfatteren ikke har skrevet om dem på en stund. Hustvedt klarer det.

I The Sorrows of an American møter vi de norsk-amerikanske søsknene Inga og Erik. De er like nøyaktig skildret som Leo var i What I Loved (på norsk: Det jeg elsket) for fem år siden. Hustvedts nyeste bok er ikke en oppfølger til den forrige, men den foregår innenfor samme miljø i New York City. Den nye boken omfatter fire generasjoner, men handlingen går over bare ett år. Det er det året Inga kaller “the year of secrets”. The Sorrows... handler om alles hemmeligheter.

Erik er psykolog og forteller i første person. Sammen med Inga leter han etter sin avdøde fars hemmeligheter. Mysteriet om faren blir imidlertid stadig satt på pause mens Erik følger sidespor. Han vil også fortelle om sine pasienter, bøkene til søsterens døde ektemann og hvor opprørt hans niese er etter at hun opplevde 11. september 2001. Hustvedts komplekse og troverdige skikkelser kan ikke forstås uten sine drømmer, kunstverk, samtaler, doktorgrader og bøker. Derfor handler boken om mye mer enn den ytre handlingen. Mysteriet driver riktig nok handlingen fremover, men først og fremst distraherer det hovedpersonene fra deres egen ensomhet.

Det er fristende å lete etter bokens dypere mening: Er den en kommentar om norsk-amerikanere eller det amerikanske samfunnet? Tittelen forteller at det handler om spesielt amerikanske sorger. Hustvedt har brukt sin norske fars dagboknotater direkte i boken. Tanker om 11. september blandes med sanne historier om norsk-amerikanere under depresjonen. Psykologen Erik overanalyserer dessuten sin egen hverdag. Leseren kan dermed få et inntrykk av at naboens tegninger, søsterens drømmer og pasientenes klager er ledetråder i samme mysterium.

Det er imidlertid beskrivelser av personer som er Hustvedts store styrke. Jeg foretrekker derfor å lese boken som en god person- og miljøskildring, ikke en kommentar eller allegori. En tenåring må kunne være traumatisert av et møte med terrorisme uten at det nødvendigvis må leses som en kommentar til amerikansk utenrikspolitikk. Når Erik innlemmer norske ord i sitt språk, er det en del av hans kulturarv og personlighet. Jeg vil ikke lese det som et forsøk på å fortelle leseren noe universelt om norske innvandrere.

What I Loved er fortsatt Hustvedts beste roman. The Sorrows of an American føles litt uferdig. Mysteriene løses, slik at den ytre handlingen får en avslutning, men Erik holder fortsatt egne hemmeligheter fra leseren. Når karakterene bærer handlingen, savner jeg en mer kompleks utvikling hos fortelleren. Historien om psykologen som trenger psykolog har blitt fortalt før.

Samtidig er Eriks og Ingas ensomhet akkurat så sår som den skal være. Å lese boken er som å besøke en deprimert venn. Det gjør kanskje vondt, men man bryr seg nok til at man gjør det likevel.

Posted by Julie at 4:51 PM | TrackBack

March 3, 2009

Reuniting with Leo

With a mischevious smile, Inga raised her thumb and began to enumerate the guests, lifting a finger for each: "You and your mysterious Shakespeare heroine; Mamma, Sonia, me; Henry Morris, professor of American Literature, NYU, knew Max a little, recovering after painful divorce from mad Mary. He's a wee bit stiff, but very smart. In fact, I like him a lot. We've had a date." Inga winked at Erik, then thrust up the thumb of her other hand to keep on counting: "My friend Leo Hertzberg..."

For a moment, I stopped paying attention to their conversation: Leo Hertzberg? So Leo is alive...

Inga continued:

"Yet another professor, but a retired one, from art history at Columbia, lives on Greene Street, sees poorly, but he's very interesting and extremely kind. I met him from my friend Lazlo Finkman. I've been reading Pascal to him every week for an hour or so, and then we have tea. His great sadness is that his only child, a boy, died when he was eleven. Matthew's drawings are all over the apartment."

Definitely the same Leo Hertzberg. How does Inga know Lazlo? And more importantly: Is Leo all right?

I rummaged through my purse for my smallest notebook, but realized that I was only doing so to calm myself down. There was no need to make a note of this. I would not forget it.

I haven't heard from Leo in years, and today I realized how worried I have been. I haven't tried to contact him, because I'm not crazy: I know Leo isn't real.

It might just be a novelist's greatest possible achievement: to create characters so believable that the reader desperately wants to call them to make sure they're ok and then to invite them over for wine and conversation. With What I Loved, where I first met Leo and his friends, and now with The Sorrows of an American, which makes me want to call Erik and tell him I'm lonely too, Siri Hustvedt does just that. She creates a complete, alternate world of her characters.

And so today I took a tram through Oslo and ended up in a loft in New York City, preparing for a party with Erik and his sister Inga. And my old friend Leo was on the guest list.

The first and fourth paragraph of this text were written by Siri Hustvedt in The Sorrows of an American. I have copied them, changed one word (Erik was originally I) and included them here to illustrate the experience of stepping into a novel's alternate reality.

Related post for Norwegian readers: Review of The Sorrows of an American

Posted by Julie at 9:23 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

February 26, 2009

Love in a Headscarf

I usually don't enjoy what The Guardian calls chick lit. That stuff is better in the movies, where you can concentrate on the shoes and hair and bags when the storyline becomes too silly. But I might want to read Love in a Headscarf, Shelina Zahra Janmohamed's "chick-lit memoir of her arranged marriage" - just out of curiousity.

Some quotes from the comment thread of The Guardian's article:

What strikes me is the way she describes the process in purely material terms. She 'judges' potential husbands on their looks, time-keeping and financial generocity to herself. No mention of personality, interests or compatibility. Is that what it's about?

Bridget jones didn't claim to speak or represent each and every 30-year old who happened to be single

Nor does Shelina attempt to do the same for Muslim women. It's just a story of how she finds love - why is it that as a minority writer, she suddenly is expected to carry the burden of representing each and every muslim woman in the world?

Those Muslim women living in the West who are making a free choice to act publicly like second-class citizens (in relation to men) must accept that their actions and beliefs are profoundly threatening to Western women, who are still fighting a long battle not to be second-class citizens.

Posted by Julie at 11:07 AM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

February 23, 2009

Hvordan ikke bli skrevet om på nett

Via intern-nettsiden til Høgskolen i Oslo finner jeg ut at det skal være "morgenbokbad" med lansering av en ny bok om nettskriving. Ove Dalen har skrevet "Effektiv nettskriving", og den lanseres på min skole! Fint! Det står så mye rart om nettskriving i journalistikkstudentenes pensum, så dette var på tide! Jeg skal SÅ på bokbad, og jeg skal SÅ blogge.

Eller ikke.

Arrangementet er fullt, og det ville uansett kostet meg 300 kr å komme inn.

300 kr for å få 10 % rabatt på en bok til 398? Ja, det er tydeligvis noen som synes det er en god deal.

Posted by Julie at 11:43 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

February 17, 2009

E-bokdebatt på Blå

Etter debatt om e-bøker på Blå i kveld, lurer jeg på om jeg ønsker meg en Kindle.

Jeg legger ut mine egne notater, men med et slags forbehold: Dette er ikke et fullstendig referat. Jeg var egentlig på debatten fordi jeg jobber med en sak om finansiering av nettaviser, og det forklarer hvorfor bloggeren Størmer og Aftenpostens Bjørkeng får mer spalteplass her i bloggen enn forfatteren Oterholm og Gyldendals Buset.

Skulle noen føle seg feilsitert, oppfordrer jeg til protester i kommentarfeltet.

Forøvrig ble visst arrangementet liveblogget.

Les også Paul Chaffey om samme tema, og alt han linker til, spesielt Eirik Newth og The Economist.

Før Kindle, skrev jeg selv om bøker på papir og skjerm.

- Bjarne Buset (informasjonssjef Gyldendal og selger sin bok via Mobipocket)

- Anne Oterholm (forfatter og leder Forfatterforeningen).

- Per Kristian Bjørkeng (journalist Aftenposten).

- Carl Størmer (blogger - www.carlstormer.com og Kindlebruker).

Størmer:

- Mange sier de liker papir, men man kan alltid ha litt papir i lomma.

Han trekker en parallell til hester og biler: man kan like lukten av hest, men det betyr ikke at man ikke kjører bil når man skal fra a til b.

Endring i forretningsmodellene er viktige, fordi denne teknologien potensielt kan endre maktforholdene i forlag. Det kan være andre mennesker som tjener penger. Amazon tilbyr for eksempel direkte publisering.

En forretningsmodell er:

-

verdiskapning

-

å ta betalt for verdien

-

å kunne beskytte seg

Bjørkeng:

Den gjennomsnittlige Kindlebruker kjøper 2,6 ganger flere bøker enn før de kjøpte Kindle. Kindle gjør hva som helst for å gjøre det enkelt å kjøpe bøker. Den er en bokhandel i seg selv. Man kan lese avisen – papirutgaven selvsagt :-) – og finne en anmeldelse, og så kan man med en gang kjøpe bøken på Kindle fra hvor som helst (i USA, i dag kan man ikke laste ned bøker til Kindle hvor som helst i Norge, fordi det ikke finnes noen avtale for boknedlasting over norske mobilnett til Kindle). Det er lavere pris enn i bokhandelen med ca. 60 %. Amazon har klart å knekke koden. Storleserne kjøper. Hvis man leser en bok i året, lønner ikke Kindle seg, men hvis man leser en bok i uken, sparer man mye. Piratkopiering kommer til å bli et stort problem.

Bjørkeng med irex, et alternativ til Kindle som finnes i Norge.

Buset:

Vi i Gyldendal gleder oss, og jeg kommer ikke til å la meg provosere i denne debatten. Internett kan kortslutte verdikjeden til forlagene ved å kutte ut mellomleddene. Forlagenes rolle blir annerledes. Blir det mulig å være forfatter hvis alt skal være gratis? For leserne blir det en himmel. Bær med deg hele verdens bibliotek. Bøkene blir aldri utsolgt. Riktig nok er det mye av verdenslitteraturen som allerede er gratis tilgjengelig på nettet. For en viss type bøker vil ikke papir forsvinne. Trenger vi bokhandelen som et sted? Det blir kanskje som fotballstadion før og etter tv. En stund tømtes fotballstadionene, men så fant man ut at man gikk glipp av noe sosialt ved å bare se fotball hjemme.

Fastpris bremser e-boken i Norge. Jeg har skrevet fem T-er som e-boken trenger:

Teknologi – en kul dings, folk faller for elektronisk blekk

Tilgjengelighet

Titler

Tilbud – en god pris

Trygghet – et “sted” der teksten er

De fem T-ene er forent i Kindle.

Hva gjør dere i dag for å møte den nye teknologien?

Foreløpig bremser vi. Det eneste fornuftige er for forlagene å samarbeide og bli enige om en digital distribusjonskanal. Da har vi en felles standard, og vi kan sørge for at verdiskapningen forblir i bransjen, ikke flytter seg ut. Vi håper en slik løsning kommer innen årets slutt.

Oterholm:

Min 16-år gamle sønn laster ikke piratkopierte bøker, fordi det er ingen han kjenner som leser. Jeg tror e-bokens lesere er interesserte i å samarbeide med forfatterne og forlagene. Derfor trenger vi ikke å ha piggtråd rundt årsverkene – altså kopibeskyttelse.

Bjørkeng:

DRM rammer først og fremst den lovlydige brukeren. Det er derfor musikkbransjen har gått bort fra det. PDF med vannmerke (som kan fjernes, slik Buset gjorde da han begynte å laste ned norske e-bøker.) innebærer at du eier filene (i motsetning til DRM, der du bare kan bruke filene innenfor bestemt teknologi.)

Størmer:

MP3 konkurrerer langs en annen akse enn CD. Vi er låst i gamle forretningsmodeller. Spotify for eksempel, tilbyr streaming. Det blir omtrent som å kjøpe strøm. Det er tre spørsmål:

-

Når skjer ting? Her er det lett å ta feil, fordi bruken av denne teknologien vokser eksponensielt.

-

Hva skjer?

-

Hvordan påvirker det oss?

Det oppsummerte svaret er at noen kommer til å skrive, noen kommer til å bearbeide, noen kommer til å fortelle at teksten finnes (markedsføre) og noen kommer til å distribuere. Men det er ikke nødvendigvis de samme aktørene som i dag.

Forlagene må kanskje kannbalisere. Det vil si å prøve nye forretningsmodeller selv om man taper penger på kort sikt. Å bryte egne mentale modeller er den store utfordringen i innovasjon. Vi er fanger fordi vi er optimalisert etter vår egen modell. Du må ha råd og tid til å innovere og eventuelt feile, og det har du ikke hvis du er optimalisert. Da kan det legges piggtråd mellom kjøper og selger, for å bruke Oterholms bilde.

Buset:

Jeg er en varm tilhenger av DRM. Det stemmer ikke at musikkbransjen “skjønte det” nå. Musikkbransjen hadde uflaks. Forlagsbransjen er heldig fordi det er vanskeligere å kopiere1 og fordi vi har mer konservative kunder. Det ligger en viktig symbolverdi i at forfattere skal kunne si at de eier noe.

Fastprisavtalen?

Bjørkeng:

Fastprisavtalen er bokbransjens verste fiende. Vi må ha forlag og forfattere, men 70 % av bokprisen i dag går til distribusjon. I bakgrunnen lurer The Pirate Bay. Det stemmer ikke at musikk er det letteste å kopiere. Bøker er det letteste å kopiere. Bøker er så små (i filstørrelse). Alle moderne engelskspråklige bestselgere kan distribueres i én fil. Jo før forlagene forstår dette og prøver å lage et godt system, jo mindre taper de til piratene.

Oterholm:

Teknologi som Kindle og andre e-boklesere kan gjøre det lettere å kjøper bøker i den lange halen. Det som vil koste penger er at noen må fortelle om bøkene i den lange halen (markedsføring).

Størmer:

Av dere som sitter i panelet med meg, tror jeg bare det er Oterholm som overlever denne teknologiutviklingen. “Vi har lagd utstyret til hester, klart vi skal lage bildeler” – den tankegangen fungerte ikke da, og det er ikke sånn det fungerer nå. Forlagene har ingen merkevare! Tenk hva dette kan gjøre for fagbøker, hvis man for eksempel kan kjøpe dem kapittelvis. Gode redaktører vil det fortsatt være bruk for. I dag tjener de luselønninger i Norge, men de kommer ikke til å forsvinne.

Buset:

Jeg skal som sagt ikke bli “trukket opp” i dag. Hvis forlagene forsvinner, så får de gjøre det.

Om fastpris: Vi skal i hvert fall ikke ha en situasjon der e-bøker koster 399,- og konkurrerer med papirutgaver som koster det samme.

Spørsmål fra salen begynner. Resten av kommentarene mine er bare sporadiske punkter som jeg syntes var spesielt interessante:

Første spørsmål er om hvordan boken vil se ut i fremtiden: Vil den inneholde musikk? Video? Linker til ordforklaringer og bakgrunnsinformasjon?

Buset:

Var det en jobbsøknad? Jeg tror du har svart på ditt eget spørsmål. JA!

Størmer:

Kindle er en uforstyrret leseropplevelse. Alle snakker om hot spots, men jeg er like opptatt av å finne cold spots – selv om den allerede har innebygget ordbok og linker til wikipedia.

Størmer med sin Kindle.

Bjørkeng:

Elektronisk blekk kan ikke vise farger. Dessuten vil man, når man leser en roman, leve seg inn i forfatterens verden. Men wikilinker i fagboker bør bli en vinner.

Bare vent til Blindern skal velge mellom å bruke 4000,- på mange kilo pensum eller piratkopiere pensum.

I dag er bøker kontrollert av tykkelse på selve boken som gjenstand. Hva om leseren betaler etter time? Kan bøker bli lengre?

Morten Jørgensen, forfatter (mer kommentar enn spørsmål):

Min neste roman er med linker.

Jeg er villig til å vedde på at amerikansk bokbransje kontrollerer den norske innen 10 år slik forlagene holder på nå.

Det er ikke snakk om at papirboken dør eller lever. Vinyl lever jo fortsatt, og Director's Cut filmer lever som dvder selv om folk laster ned filmer. Men trærne kan glede seg over at papirboken solgt i det omfanget den er i dag, dør.

Bokbransjen lever på kjempedyre lærebøker – få det vekk!

Fildeling for Afrika! Gi Asia og Afrika gratis fildeling nå! Hev spørsmålene opp på et politisk plan. Eller la alle som betaler for bredbånd gi 50 ekstra kroner og fordel blant forfattere og forlage i ettertid.

Buset:

Gutenberg gjorde det så lett å kopiere at man måtte oppfinne opphavsretten for å lage incitament til å skape noe i det hele tatt.

Størmer:

Innovasjoner kommer der etablerte aktører ikke tjener penger. Bloggere er eksempler på skriveføre som kan tjene penger selv.

Kommentarer/spørsmål fra salen:

Forslag til forretningsmodell for forlag: De kan drive med oversettelse, signeringsturnéer og salg av prakteksemplarer.

Størmer:

Det vil alltid være en som leser. Det vil alltid være en som skriver. Det i midten forandrer seg.

Få hele verden som leser – skriv på engelsk!

Reklame i litteraturen er kanskje en løsning? :-)

Bøkene jeg er glad i, vil jeg i hvert fall ikke ha på papir. De vil jeg ha på Kindle, slik at jeg alltid har dem med meg.

1Nå ble jeg plutselig usikker på om det var det han sa, fordi det høres ikke logisk ut. Sannsynligvis mener han papirbøker. Før teksten er digitalisert, er den vanskelig å piratkopiere. Så vidt jeg husker, nevnte også Buset at "papirboken som fysisk gjenstand er kanskje den mest effektive kopisperren vi har". Med en gang teksten er digital, er den imidlertid fantastisk lett å kopiere. Ctrl C + Ctrl V.

Posted by Julie at 11:32 PM | Comments (6) | TrackBack

January 12, 2009

Novels of 2008

Some novels I read and enjoyed in the past year - more info on each one later.

On Beauty by Zadie Smith

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

Les Misérables by Victor Hugo (read it here)

If On a Winter's Night a Traveller by Italo Calvino

Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

Life of Pi by Yann Martel

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

(Looking at the list, I'm struck by the authors' interesting names. I need to change mine, I think.)

Posted by Julie at 11:28 PM | Comments (2) | TrackBack

December 15, 2008

Anne-Cath. Vestly

The first thing that happened to me today was that I found out that Anne-Cath. Vestly is dead. She was a Norwegian author of children's books. As far as my childhood was concerned, she was the only Norwegian author of children's books.

I grew up making way for ducklings, scared and fascinated by robbers, and best friends with Anne Shirley. I generally preferred my fiction to take me to someplace long ago and far away - there was enough realism in the real world.

Norway, my home country, was long ago and far away. Except for summer (vacation, so not real life) and my parents' memories (long ago, and they were grown-ups), it was far more distant than Prince Edward Island and the Boston Public Garden.

I can't think of any other Norwegian author who meant more to me. Because, even though I didn't think about this at the time, looking back, Vestly's fiction was a window into what growing up "back home" was like.

And I'm glad that I pictured Norway the way she did. I'm glad that in Norway, families with eight children lived in one-room apartments in Oslo and still took care of their mormor* who was afraid of taking the tram through town. And that a little girl who played the violin had no father and a mother who worked as a janitor in their apartment building. And that in the same apartment building, another little girl's father stayed at home studying and eventually defending his doctoral dissertation while her mother worked as a lawyer. Although she caused controversy, Vestly's books never seemed overly political. They just told the truth about how children live and think.

The week before Vestly died, I talked about her with my family. Just this Saturday, some of her characters came up in a conversation with my best friend. Today, friends are grieving for "the end of their childhood" in Facebook statuses. I know we'll all read her books to our children.

Links

- Wikipedia in English on Anne-Cath. Vestly

- Another English-language post about Anne-Cath. Vestly

- My dad's post about her, in Norwegian

Related posts

- Well, it's over

- Books I read too early

- Just read!

- Svar på boksspørsmål (my first blog post ever was about books, in Norwegian)

* Mormor = mother's mother, grandmother

Posted by Julie at 11:22 PM | TrackBack

November 23, 2008

Middlesex

I read Middlesex earlier this fall, and now I think the author Jeffrey Eugenides could tell me any kind of story and I would love it. I won't go into detail when it comes to plot. The Amazon review basically sums up my own thoughts on the book - including the sadness I felt when it was almost over. So here is an excerpt.

Desdemona had found Lefty on our kitchen floor, lying next to his overturned coffee cup. She knelt beside him and pressed her ear to his chest. When she heard no heartbeat, she cried out his name. Her wail echoed off the kitchen's hard surfaces: the toaster, the oven, the refrigerator. Finally she collapsed against his chest. In the silence that followed, however, Desdemona felt a strange emotion rising inside her. It spread in the space between her panic and grief. It was like a gas inflating her. Soon her eyes snapped open as she recognized the emotion: it was happiness. Tears were running down her face, she was already berating God for taking her husband from her, but on the other side of these proper emotions was an altogether improper relief. This was it: the worst thing. For the first time in her life my grandmother had nothing to worry about.

Emotions, in my experience, aren't covered in single words. I don't believe in "sadness", "joy," or "regret." Maybe the best proof that the language is patriarchal is that it oversimplifies feeling. I'd like to have at my disposal complicated hybrid emotions, Germanic train-car constructions like, say, "the happiness that attends disaster." Or: "the disappointment of sleeping with one's fantasy." I'd like to show how "intimations of mortality brought on by aging family members" connects with "the hatred of mirrors that begins in middle age." I'd like to have a word for "the sadness inspired by failing restaurants" as well as for "the excitement of getting a room with a minibar." I've never had the right words to describe my life, and now that I've entered the story, I need them more than ever. I can't just sit back and watch from a distance anymore. From here on in, everything I'll tell you is colored by subjective experience of being part of events.

From Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, (pages 216-217 in the 2003 Bloomsbury paperback edition)

Posted by Julie at 12:44 PM | TrackBack

July 23, 2008

Pia Haraldsen feil - Del 2

"Your manuscript is both good and original. But the part that is good is not original, and the part that is original is not good." Samuel Johnson sa visst aldri dette, men jeg sier det nå. Det beskriver nemlig boken Pias Bekjennelser så godt. Jeg lovet en anmeldelse, og her er den...

La meg presisere et par ting. For det første, denne boken forandret mitt liv. Jeg ble nemlig solbrent, og senere ble jeg faktisk brun. Det skjer ikke. For det andre, mitt førsteinntrykk av Pia Haraldsen var positivt. Jeg satt og irriterte meg over hvor grå alle gjestene i Ingrid Alexandras barnedåp så ut, da hun dukket opp og smilte selvsikkert til fotografene. Skal du gå på en rød løper, skal du gjøre det skikkelig. Du skal ikke se ned i bakken med lutede skuldre som om du intenst ønsker deg vekk. Ja, slike kjendiser som er kjent for å være kjendiser er litt irriterende, men jeg lar meg likevel imponere av at hun har fått det til, og at hun gjør alt hun gjør med stil - selv om rosa minikjole og Hello Kitty smykke ikke er min stil.

Å slakte en bok med rosa glitterforside for at den inneholder "overfladiske" ting som skjønnhetstips, blir for latterlig. I motsetning til Vendelas "Beauty Bible", inneholder denne boken råd mange har godt av å få med seg. For Pia har helt rett i at alle bør kle seg etter sin egen figur og stil, ikke etter ukens trender. Og ikke minst at jenter som hele tiden snakker om at de har stygge lår, etter hvert vil være kjent for sine stygge lår, om ikke annet fordi det er det eneste de snakker om. Det er denne selvsikkerheten som gjør deler av "Pias Bekjennelser" gode. Dette er jo ting jeg selv har blogget om, og som jeg nesten hver dag prøver å tankeoverføre til tyske og amerikanske turistdamer. Med andre ord: det er ikke spesielt originalt.

Og med en gang det blir originalt, blir det også fryktelig dårlig. Ikke bare kjedelig, men også provoserende og raserifremkallende - og den kombinasjonen er sjelden. For i bokens siste halvdel, får vi svaret på "Hva slags fraser kan du lire av deg om både kunstverk og utenrikspolitikk og få det til å høres troverdig ut?" Eller: hvordan lure Jonas Gahr Støre til å tro at man bryr seg.

For det er klart man ikke bryr seg. Pia skriver rett ut at det eneste interessante med utenrikspolitikk er Jonas og Barack, men at man likevel bør unngå å snakke om sminke og kjendiser hele tiden - selv om det selvsagt er det man helst vil. Man er jo jente! Da forstår man ikke før man har lest det med rosa skrift: at man skal følge med på scenen når man er på teater, og at det kan lønne seg å "lese en kronikk i ny og ne". Dette er nøyaktig like nedverdigende som tanken på at kvinner skal utdanne seg kun for å møte velutdannede menn.

I de fleste mote- og skjønnhetsblader består første halvdel av retusjerte bilder av modeller med kropper som 13-årige gutter og siste halvdel av artikler om hvor viktig det er å vise "ekte kvinner" i motereportasjer. I Pias bok handler første halvdel om å være seg selv, andre halvdel om at vi alle er helt like, men at vi heldgvis kan lure menn til å tro noe annet. Og det minner meg om et annet artig sitat, nemlig Dorothy Parkers "You can lead a whore to culture, but you can't make her think."

Misforstå meg ikke. Det er ikke horete å innse at folk kan være overfladiske, å ta konsekvensen av denne innsikten og så prøve å nå så langt man bare kan. Men er man så smart som jeg tror Pia Haraldsen egentlig er, skal man holde seg for god til å oppfordre til dumhet. Spesielt hvis man ønsker å bli husket som noe annet enn "sminkedokka fra Snarøya" - som hun faktisk påpeker at hun er blitt (feilaktig!) anklaget for å være. Jeg har derfor to ting å si til denne bokens lesere:

Hvis sko er like viktig som utenrikspolitikk, hvorfor skal man late som om man er mer opptatt av utenrikspolitikk enn sko? Dersom du pugger "Pias Bekjennelser" for å ha noe interessant å si til en date, fortjener du ikke at den daten har noe til felles med Jonas Gahr Støre (og dette sier jeg som en Interjente som har drukket kaffe med fremtidens Jonaser).

Posted by Julie at 10:52 AM | TrackBack

July 8, 2008

Pia Haraldsens feil

Min Facebook status: Julie er solbrent (og skylder på Pia Haraldsen.)

Hvorfor? Jeg leste hele boken til Pia Haraldsen mens jeg lå på en flytebrygge utenfor Malmøya. Det tok ikke veldig lang tid å komme gjennom den boken, men lang nok tid til at jeg burde hatt mer/sterkere solkrem. Bikinien min matchet forsiden. I ettertid matchet huden min rammen på forsiden.

Ja, men hvorfor gjorde du DET da? Pia Haraldsens bok var årsak til en liten slåsskamp diskusjon ved en middag hos familien min for noen måneder siden. Min far og jeg hadde begge lest om den i Morgenbladet, og vi var skeptiske. Min mor og en av mine søstre forsvarte boken. Ingen av oss hadde lest den på dette tidspunktet, men da den viste seg å være i mine foreldres hus da jeg besøkte dem på en fridag, måtte jeg bare finne ut hvem av oss som hadde rett.

Og hvem hadde rett? Vel...

Posted by Julie at 12:53 AM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

October 11, 2007

First sentence

I "Searched inside" The Myth of the Rational Voter by Bryan Caplan at Amazon.com. This is the first sentence:

What voters don't know would fill a university library.

Well, I certainly hope so. If you can't fill a university library with stuff people don't know yet, what's the point?

Posted by Julie at 10:09 PM | TrackBack

August 26, 2007

This week

- Cooking by numbers which gives you possible recipes after you've given them a list of what's in your kitchen. I could at least make "an apple on its own" using the following recipe: 1. Take apple and examine for signs of wear and tear. 2. Put your coat on and go down the local shop or supermarket. 3. Whilst walking chew on your apple. Stop eating when you get to the pips and stalk. Throw the stalk in the bin and get some food.

- "The only thing that interferes with my learning is my education." and other Einstein quotes

- Why Can't I Own Canadians?

- Info bare for de sterke "Paradoksalt nok finner Google frem til relevant informasjon på norge.no mye raskere og enklere enn dersom brukeren selv skal navigere seg frem på norge.no," skriver informasjonsrådgiver Knut Natvig. Statens nettsider er for dårlige.

- Hasj er farlig Så det så. Men det forbindes fortsatt med "politisk motkultur og høy utdanning" og nesten halve Oslo prøver det innen de fyller 30.

- The Complete Polysyllabic Spree by Nick Hornby. It makes me very happy. So much so that I don't want to pick just a few things to say about it. I'll either have to give it its own blog post, or just tell you to read it for yourself. You can read the introduction here.

I watched

- Middle East History I can't help but think while watching this: The area we call the Middle East (and maybe especially Isreal) has been controlled by so many different empires that if having once controlled a territory sometime in history gives you rights to controlling it now, then ANYONE can claim these areas. Shouldn't this be obvious to anyone using that kind of argumentation? It can apparantly be explained in 90 seconds.

- Olsenbanden Fordi jeg ikke fikk lov til å gå glipp av denne viktige siden av norsk kultur (etter et dansk konsept riktig nok).

- Pan's Labyrinth According to Kermode: "If you're only going to see one movie this year, first of all what's wrong with you? And secondly, it should be Pan's Labyrinth." And I loved it. After all, it's Narnia for grown-ups, with history, fantasy, seriously scary monsters, and a lead actress who does a great job.

I listened to

- Kermode. Well, actually I always do, but I haven't written about him yet. He is fantastic, especially when he really dislikes a movie and rants. I wish he would do that for more than just movies. I wish there were Kermode podcasts for books, politicians, newspaper articles, buses, exam grades, friends, family members, random acquantances and shoe prices.

Posted by Julie at 10:38 AM | Comments (4) | TrackBack

August 23, 2007

Future wish

"Hey, great idea: if you have kids, give your partner reading vouchers for Christmas. Each voucher entitles the bearer to two hours' reading time while the kids are awake. It might look like a cheapskate present, but parents will appreciate that it costs more in real terms than a Lamborghini."

I must remember this in the future.

Quote from the fantastic Polysyllabic Spree by Nick Hornby.

Posted by Julie at 8:46 AM | TrackBack

August 13, 2007

Advice from Hemingway

Advice I intend to follow, from Hemingway. I suppose I could call him one of my heroes, although I generally make a point of not having those.

On Writing:

If a writer knows enough about what he is writing about, he may omit things that he knows. The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one ninth of it being above water.

My aim is to put down on paper what I see and what I feel in the best and simplest way.

When writing a novel a writer should create living people; people not characters. A character is a caricature.

On Life:

Always do sober what you said you'd do drunk. That will teach you to keep your mouth shut.

Never go on trips with anyone you do not love.

Biography beneath the fold. (This is an abridged version of the text you can find here, but it's still very long for a blog post. The highlighting is from when I studied Hemingway in high school.)

At the time of Hemingway's graduation from High School, World War I was raging in Europe. The United States joined the Allies in the fight against Germany and Austria in April, 1917. When Hemingway turned eighteen he tried to enlist in the army, but was deferred because of poor vision. When he heard the Red Cross was taking volunteers as ambulance drivers he quickly signed up. He was accepted in December of 1917, left his job at the paper in April of 1918, and sailed for Europe in May. In the short time that Hemingway worked for the Kansas City Star he learned some stylistic lessons that would later influence his fiction. The newspaper advocated short sentences, short paragraphs, active verbs, authenticity, compression, clarity and immediacy. Hemingway later said: "Those were the best rules I ever learned for the business of writing. I've never forgotten them."

Hemingway first went to Paris upon reaching Europe, then traveled to Milan in early June after receiving his orders. The day he arrived, a munitions factory exploded and he had to carry mutilated bodies and body parts to a makeshift morgue; it was an immediate and powerful initiation into the horrors of war. Two days later he was sent to an ambulance unit in the town of Schio, where he worked driving ambulances. On July 8, 1918, only a few weeks after arriving, Hemingway was seriously wounded by fragments from an Austrian mortar shell which had landed just a few feet away. At the time, Hemingway was distributing chocolate and cigarettes to Italian soldiers in the trenches near the front lines. The explosion knocked Hemingway unconscious, killed an Italian soldier and blew the legs off another. What happened next has been debated for some time. In a letter to Hemingway's father, Ted Brumback, one of Ernest's fellow ambulance drivers, wrote that despite over 200 pieces of shrapnel being lodged in Hemingway's legs he still managed to carry another wounded soldier back to the first aid station; along the way he was hit in the legs by several machine gun bullets. Whether he carried the wounded soldier or not, doesn't diminish Hemingway's sacrifice. He was awarded the Italian Silver Medal for Valor with the official Italian citation reading: "Gravely wounded by numerous pieces of shrapnel from an enemy shell, with an admirable spirit of brotherhood, before taking care of himself, he rendered generous assistance to the Italian soldiers more seriously wounded by the same explosion and did not allow himself to be carried elsewhere until after they had been evacuated." Hemingway described his injuries to a friend of his: "There was one of those big noises you sometimes hear at the front. I died then. I felt my soul or something coming right out of my body, like you'd pull a silk handkerchief out of a pocket by one corner. It flew all around and then came back and went in again and I wasn't dead any more."

Hemingway's wounding along the Piave River in Italy and his subsequent recovery at a hospital in Milan, including the relationship with his nurse Agnes von Kurowsky, all inspired his great novel A Farewell To Arms.

When Hemingway returned home from Italy in January of 1919 he found Oak Park dull compared to the adventures of war, the beauty of foreign lands and the romance of an older woman, Agnes von Kurowsky. He was nineteen years old and only a year and a half removed from high school, but the war had matured him beyond his years. Living with his parents, who never quite appreciated what their son had been through, was difficult. Soon after his homecoming they began to question his future, began to pressure him to find work or to further his education, but Hemingway couldn't seem to muster interest in anything.

He had received some $1,000 dollars in insurance payments for his war wounds, which allowed him to avoid work for nearly a year. He lived at his parent’s house and spent his time at the library or at home reading. He spoke to small civic organizations about his war exploits and was often seen in his Red Cross uniform, walking about town. For a time though, Hemingway questioned his role as a war hero, and when asked to tell of his experiences he often exaggerated to satisfy his audience. Hemingway's story "Soldier's Home" conveys his feelings of frustration and shame upon returning home to a town and to parents who still had a romantic notion of war and who didn't understand the psychological impact the war had had on their son.

The last speaking engagement the young Hemingway took was at the Petoskey (Michigan) Public Library, and it would be important to Hemingway not for what he said but for who heard it. In the audience was Harriett Connable, the wife of an executive for the Woolworth's company in Toronto.

As Hemingway spun his war tales Harriett couldn't help but notice the differences between Hemingway and her own son. Hemingway appeared confident, strong, intelligent and athletic, while her son was slight, somewhat handicapped by a weak right arm and spent most of his time indoors. Harriett Connable thought her son needed someone to show him the joys of physical activity and Hemingway seemed the perfect candidate to tutor and watch over him while she and her husband Ralph vacationed in Florida. So, she asked Hemingway if he would do it.

Hemingway took the position, which offered him time to write and a chance to work for the Toronto Star Weekly, the editor of which Ralph Connable promised to introduce Hemingway to. Hemingway wrote for the Star Weekly even after moving to Chicago in the fall of 1920. While living at a friend's house he met Hadley Richardson and they quickly fell in love. The two married in September 1921 and by November of the same year Hemingway accepted an offer to work with the Toronto Daily Star as its European corespondent. Hemingway and his new bride would go to Paris, France where the whole of literature was being changed by the likes of Ezra Pound, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein and Ford Maddox Ford. He would not miss his chance to change it as well.

The Hemingways arrived in Paris on December 22, 1921 and a few weeks later moved into their first apartment at 74 rue Cardinal Lemoine. It was a miserable apartment with no running water and a bathroom that was basically a closet with a slop bucket inside. Hemingway tried to minimize the primitiveness of the living quarters for his wife Hadley who had grown up in relative splendor, but despite the conditions she endured, carried away by her husbands enthusiasm for living the bohemian lifestyle. Ironically, they could have afforded much better; with Hemingway's job and Hadley's trust fund their annual income was $3,000, a decent sum in the inflated economies of Europe at the time. Hemingway rented a room at 39 rue Descartes where he could do his writing in peace.